Mandated Reporting

Mandated reporting laws require certain professionals to report known or suspected child abuse or neglect to a state’s child protection agency (CPS). Though it varies by state, virtually all of them cover social workers, doctors, nurses, teachers, childcare providers, and law enforcement officers. Nationally, nearly sixty percent of all reports of child abuse and neglect are filed by mandated reporters.

Overview

Document published by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services explaining federal mandated reporting laws and how the laws vary from state to state.

Substance-Exposed Newborns

- 42 U.S.C. § 5106a et seq. — Child Abuse Protection and Treatment Act (CAPTA)

CAPTA is a federal law that allocates funding to state child protection (CPS) agencies, requiring states to agree to a meet certain federal standards in order to receive the funds for child abuse prevention and neglect. In 2003, Congress added a condition requiring states to develop “policies and procedures” for the reporting of “infants born with and identified as being affected by illegal substance abuse or withdrawal symptoms resulting from prenatal drug exposure.” To receive the federal funds, the state must maintain a child protective services system that includes some mechanism for health care providers to notify the state of the “occurrence” of substance-exposed newborns. States can decide exactly how to comply with the reporting condition; some states (at least the ones that didn’t already have them) have passed specific laws, while others include the requirement in their CPS agency’s written policies, rules, or regulations. The state must establish a “plan of safe care” for affected infants, though more specific details of implementation are left to the state. CAPTA does not define the terms “affected by illegal substance abuse” or “withdrawal symptoms,” nor does it explain the significant difference between being “affected … as a result of exposure” (implying a symptom, or actual harm) and being “exposed” to a drug (as would indicate a positive drug test, in the absence of visible signs). CAPTA does not direct states nor hospitals to define a “drug-affected newborn” as abused or neglected.

Drug-Exposed Children

The National Alliance for Drug Endangered Children (National DEC) is a non-profit organization that grew out of local DEC efforts in twelve states involving collaborations between law enforcement, social services, attorneys, and clinicians and receives both public and private funding. National DEC defines “drug endangered” to mean children who are “at risk of suffering physical or emotional harm as a result of illegal drug use, possession, manufacturing, cultivation, or distribution. They may also be children whose caretaker’s substance misuse interferes with the caretaker’s ability to parent and provide a safe and nurturing environment.” The organization doesn’t make distinctions between types of substance nor between frequency and manner of use (such as use ≠ abuse). DEC groups in more than half of the states have successfully lobbied to create or enhance criminal penalties for drug crimes such as sale, distribution, and sometimes possession, when a child is present. The driving force behind these laws was evidence that children living in makeshift methamphetamine laboratories face unsafe conditions, including exposure to toxic chemicals and fumes, and crime-related hazards. DEC also developed a medical protocol for “decontaminating” a child after removal to CPS custody. Yet not all are specifically tailored to address a child’s specific exposure to methamphetamine; some were enacted using broad definitions of “controlled substances” that cover all scheduled drugs. In at least 11 states, the crime of child endangerment expressly includes exposing a child to the manufacture, possession, or distribution of “illegal drugs.”

President Obama’s 2010 National Drug Control Strategy established the Federal Interagency Task Force on Drug Endangered Children, which includes participants from the U.S. Department of Justice, Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Education, Department of Transportation, Department of Homeland Security, Office of National Drug Control Policy, and other federal agencies. It has primarily focused on the development of training courses for law enforcement personnel. The task force has defined “drug endangered child” to mean:

“…a person, under the age of 18, who lives in or is exposed to an environment where drugs, including pharmaceuticals, are illegally used, possessed, trafficked, diverted, and/or manufactured and, as a result of that environment: the child experiences, or is at risk of experiencing, physical, sexual, or emotional abuse; the child experiences, or is at risk of experiencing, medical, educational, emotional, or physical harm, including harm resulting or possibly resulting from neglect; or the child is forced to participate in illegal or sexual activity in exchange for drugs or in exchange for money likely to be used to purchase drugs.”

Notably, this definition limits dangerous exposure to that of drugs being used illegally, but does not include exposure to substances that are lawfully used. Still, because federal law does not permit any lawful use of marijuana, state-legal marijuana use and possession is still considered illegal under federal law.

Child Welfare Cases in Family Court

Once a child abuse or neglect proceeding is in front of a judge in juvenile or family court, federal law (CAPTA) requires that the court appoint a guardian ad litem (GAL) to represent the child. In custody cases, a parent can request a GAL for their child(ren) if one has not already been appointed. In some states, the GAL must be a licensed attorney, and in others, need only be a trained advocate. The GAL is appointed by the state to assess the situation and the child’s needs, and make recommendations to the court on the child’s behalf. Parents cannot directly hire a GAL to represent their child(ren), though they may be required to pay the costs of the GAL’s services. It may be possible for a parent to request that the court appoint a new GAL, but the decision to replace one that has been appointed is up to the judge.

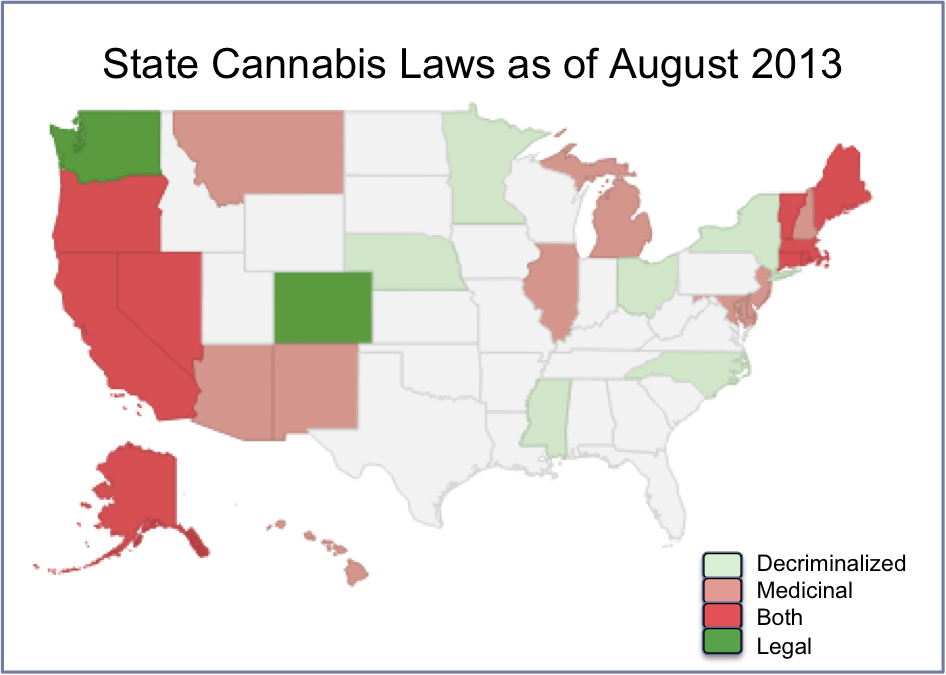

Marijuana Laws

Prior to 1970, there was no federal law criminalizing marijuana possession. It was regulated and effectively prohibited by the tax requirements of Marijuana Tax Act of 1937 as well as state criminalization laws, many of which were adopted during the 1930s as well. The Marijuana Tax Act was held unconstitutional in a 1969 Supreme Court case, Leary v. U.S. (395 U.S. 6 (1969)), which held that the federal law’s requirement that marijuana possessors register with the federal government violated their right against self-incrimination, since in doing so they were necessarily admitting to having violated criminal laws of the states. In the meantime, drug prohibition had become a popular political cause, with nearly a hundred countries signing onto the 1961 amendments to the United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. In 1970, Congress enacted the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention & Control Act, which created the first federal drug crimes. It contains the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), establishing five Schedules of drugs according to three factors: (1) potential for abuse, (2) medical use, and (3) severity of harm from abuse. Marijuana, or its active ingredient, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), was designated Schedule I—the most restrictive. According to the CSA, there is no established medical use of any Schedule I substance, and possession is punished harshly. The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) was created in 1973 to implement the provisions of the CSA and its successor laws. Other federal agencies bound by the Controlled Substances Act include the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), which controls the supply of controlled substances for clinical research, and the Office on National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP). Because of marijuana’s status as a Schedule I substance, it is extremely difficult to conduct any medical research on its therapeutic benefits, as demonstrated by the recent federal case, Craker v. DEA.